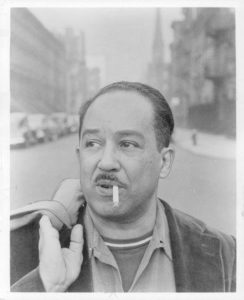

Langston Hughes

(1902–1967), the famous African American poet and playwright, who

graduated from high school in Cleveland; and cut his creative teeth at Karamu, where several of his acclaimed plays were first produced, and would become the foremost poet of the Harlem Renaissance. “His poetry and fiction portrayed the lives of the working-class blacks in America, lives he portrayed as full of struggle, joy, laughter, and music,” says Wikipedia. “Permeating his work is pride in the African-American identity and its diverse culture. He confronted racial stereotypes, protested social conditions, and expanded African America’s image of itself. Hughes stressed a racial consciousness and cultural nationalism devoid of self-hate. His thought united people of African descent and Africa across the globe to encourage pride in their diverse black folk culture and black aesthetic.

“Hughes was one of the few prominent black writers [of his day] to champion racial consciousness as a source of inspiration for black artists,” notes Wikipedia.

His 1926 collection of poems, The Weary Blues, won wide acclaim, as did his first novel, Not Without Laughter (1930), which was awarded the Harmon Gold Medal for literature.

Hughes’ poetry often incorporated the rhythms and spirit of jazz, bop, gospel and the blues. In fact he liked to give public readings his poems to the live accompaniment of jazz musicians such as Charlie Mingus and Leonard Feather. Again and again, he gave memorable expression to the thoughts, experiences and feelings of African Americans, to whom he became and immensely important figure.

One of his most beloved poems, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” Hughes works a set of stunning variations on a single motif in much the same the way an inspired jazz musician would wring lyrical statements from a repeated phrase of just a few notes. In 10 simple declarative sentences, he captures things that ring so deeply true about the indomitable spirit and wisdom, the character, the deeply rooted dignity of Africans and African Americans:

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood

in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans,

and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Langston Hughes: said to have been one of the few prominent black writers of his day to champion racial consciousness as a source of inspiration for black artists. (Plain Dealer photo)

The sentiments and language ring as true and feel as naturally said today, as they did when they first appeared (hard to believe it) a century ago in 1921 in The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP. Critic David Littlejohn puts it astutely: It was, he says, “by retaining his own keen honesty and directness, his poetic sense and ironic intelligence, that he maintained though four decades a readable newness distinctly his own.”

Besides poetry, novels, and seven collections of short stories, including The Ways of White Folks (1934), Hughes authored a number of important essays and a long-running newspaper column, as well as a pair of highly readable autobiographies. In The Big Sea, he recalls his high school years in Cleveland, time in Paris and Cuba, and his not-uncomplicated friendships with W.E.B. DuBois and Zora Neale Hurston. In as second volume, I Wonder as I Wander, he recounts his eyer-opening travels to Spain, Russia and China.

A series of popular columns he wrote for The Chicago Defender frequently featured one Jesse B. Semple (better known as “Simple”), a fictional character living in Harlem who is an endless fount of stories he will share in return for a drink. These tales, by turns funny and poignant, brilliantly captured the challenges faced by a poor black man living in a predominantly white society. Collected in a series of popular books titled Simple Speaks His Mind (1950), Simple Takes a Wife (1953), Simple Stakes a Claim (1957) and Simple’s Uncle Sam (1965), they won the hearts of a national audience, and inspired a play, Simply Heavenly, that was to run Off-Broadway for 169 performances before finding a second life in regional theaters.

Hughes turned out at least a dozen major plays. In fact, he holds the distinction of being the only one of Cleveland’s “Past Masters” who was nominated for recognition, and is being so honored, both as an author of fiction and non-fiction and as a successful playwright.

Oberlin professor and Africana specialist Gillian Johns sums up the case for honoring Hughes: “We all know the important place that poet, novelist, essayist, playwright, and autobiographer Langston Hughes holds in African American and American literary history, but we should also remember him as a proud and grounded rust-belt, working-class oriented author who spent time during his formative years in Cleveland and Oberlin and perfectly embodied the region’s ethos of fairness and plain talk. His landmark essay, ‘The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain’ (1926), is still cited as a key moment of self definition in black aesthetics, and Hughes toured the South reading and distributing copies of his poems, to help build an audience for African American poetry that would serve many later poets.

“Some academics have seen Hughes’s work as unfortunately limited by the voices, music, and settings of ordinary black folks. And yet figures like Jesse B. Simple (the name of his armchair philosopher whose voice and viewpoints are at the center of a column published for forty years in in The Chicago Defender) have captured the American scene—and all its racial and class contradictions—with the ‘drylongso’ common sense and wisdom that we could use much more of in every age!”