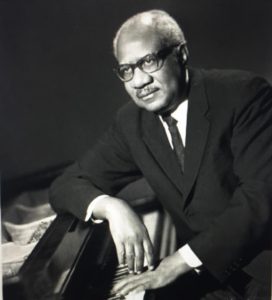

Howard Swanson

(1907–1978), whose settings of the poems of Langston Hughes—among

them, “Joy,” “In Time of Silver Rain,” “Night Song,” “Pierrot” and “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”—are considered by many the definitive interpretations of the poet’s work. William Flanagan found Swanson’s songs “sensitive, intimate, and evocative.” New York Herald Tribune critic/composer Virgil Thomson called Swanson “a composer whose work singers (and pianists, too) should look into. It is refined, sophisticated of line and harmony in a way not at all common among American music writers. His songs have an acute elaboration of thought and an intensity for feeling that recall Fauré.”

In 1916, when Howard was eight, the Swanson family left Atlanta for Cleveland, where he graduated from Glenville High School in 1925, taking over the job of supporting the family when his father died. Determined to expand his musical horizons, in 1930 he began to study piano at the Cleveland Institute of Music and composition with Herbert Elwell, who had studied in Paris with the legendary Nadia Boulanger. In 1938, Swanson himself would travel to Paris to study with Boulanger as a Rosenwald Fellow.

“The year 1950 proved to be crucial in Swanson’s career,” notes the New Georgia Encyclopedia. That January the great contralto Marian Anderson performed his 1942 setting of the celebrated Langston Hughes poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” at New York’s Carnegie Hall, that was to become part of her repertoire. (She performed it during her farewell American tour in 1964–65.)

Swanson’s settings of Langston Hughes poems were sung at the White House by Leontyne Price for Jimmy & Rosalyn Carter.

(Fair use image used courtesy of Maurice Seymour, Center for Black Music, Columbia College, Chicago)

That summer the noted conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos heard several of Swanson’s songs at a concert and asked the composer if he might have an orchestral work for one of the famed maestro’s future concerts with the New York Philharmonic; that Fall, Mitropoulos led the world premiere of Swanson’s Symphony no. 2 (a.k.a. the Short Symphony). Audience response was enthusiastic, and Virgil Thomson praised the work for its “highly personal” nature, noting that the music spoke “clearly, warmly, modestly and at the same time with authority.” It was given the New York Music Critics Circle award as the most interesting composition of the season.

In 1952 Swanson received a grant from the National Academy of Arts and Letters and a Guggenheim Fellowship. That year the Short Symphony was performed at Severance Hall by the Cleveland Orchestra on a program with Ernest Bloch’s majestic Israel Symphony. In striking contrast, Swanson’s symphony, wrote Plain Dealer music critic Herbert Elwell, carried out “its modest intentions in an efficient, contrapuntal manner, disclosing an unassuming but distinctive personality. It is alive to current trends, discreetly acknowledging the heritage of jazz, but with something of its own to say. In its quiet, confident rhythmic flow, there were dignity, charm and engaging thoughtfulness.”

Swanson’s other important works include “The Cuckoo” Scherzo for Piano (1948), Suite for Cello and Piano (1949), Night Music (1950), Music for Strings (1952), a Concerto for Orchestra (1957), Symphony no. 3 (1969), and his settings of poems by Paul Lawrence Dunbar such as the touching, jazz-inflected lullaby, “A Death Song.”

In virtually all of his compositions, Swanson worked within the conventional forms of classical music, but he was able to infuse them with a personal style grounded in African American traditions. Swanson died in 1978. That January Leontyne Price sang his lyrical “Night Song” in a special performance at the White House. Cleveland Public Library owns scores & parts for some of Swanson’s compositions, including the never performed Variations on a Negro Theme, scored for 32 instruments. Performances of several works, including Night Music, Short Symphony, his Concerto for Orchestra, songs, & the charming piece for piano called “The Cuckoo,” can be found on Youtube: