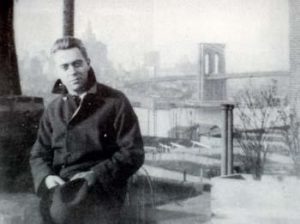

Hart Crane

(1899–1932) was considered a prophetic figure in American literature. Like his

father, Cleveland confectioner Clarence Crane, whose quest for a modern form of candy that could stand up to Ohio’s summer heat led him to invent Life Savers, Harold Hart Crane set himself a daunting challenge: to forge a poetic vision that would show a way out of the grim pessimism and cynical abandon spawned by World War I’s vast, mindless carnage.

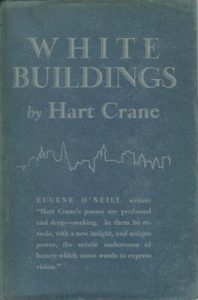

In his long poem of 1923, For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen, he used jazz rhythms to “‘unbind our throats of fear and pity’ by celebrating rather than denigrating or bemoaning the modern world,” writes Russell Elliott Murphy in American National Biography. “Through his commitment to that poetic vision”— forged as a challenge to the bleak pessimism of T. S. Eliot’s famous poem The Waste Land—“[Crane] has come to occupy an enduring place in the American literary canon.”

Among his most important poems is Chaplinesque, (“these fine collapses are not lies…”) written after viewing the great comic Charlie Chaplin’s film The Kid. Crane’s most ambitious work, The Bridge, a moving meditation on the spectacular Brooklyn Bridge, is still considered an American classic.

How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest

The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him . . .

As apparitional as sails that cross

Some page of figures to be filed away . . .

—Till elevators drop us from our day . . . .

Again the traffic lights . . . immaculate sigh of stars . . .

And we have seen night lifted in thine arms.

The idea for the poem had first come to him at the age of twenty-three while he was working for a small advertising firm in Cleveland. Its subject would be the American experience in its entirety. It would take seven years to write.

When it was done, the poem had grown into a fifty-six-page multi-section work that dealt (notes Langdon Hammer writing in The New York Review of Books) with “the tradition of New World prophecy, the frontier, the Civil War and World War I, folklore, hoboes, minstrelsy, burlesque, advertising, cinema, popular music, the nineteenth-century whaling industry, the deep time of Native American culture, and the geological formation of the North Carolina seacoast, among many other matters.

“Crane’s generation saw themselves as heralds of a new American society,” says Hammer, “more democratic, freer, and collectively dedicated to individual self-fulfillment. He understood his poem as inheriting and passing on the unfulfilled promises, the open prophecies, of America’s cultural past.” As a gay teenager, then as a young man, in Cleveland, Crane had endured shame and exclusion, dropping out of East High School as a junior and heading to New York, having promised his parents he would enroll at Columbia, and found in the city’s bohemian community a more live-and-let-live attitude. Back in Cleveland he found himself beginning to believe that, if Americans could be made to pause and contemplate their shared experience, the sheer majesty of what has been accomplished, a community based on love and mutual respect was possible.

Alas, the America of his time was not ready. And Crane eventually succumbed to despair. His body was lost at sea. But his poetry remains. And in his native Cleveland, a sculpture park has been named for him on the east bank of the Cuyahoga.

For more on the poet, see https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/hart-crane