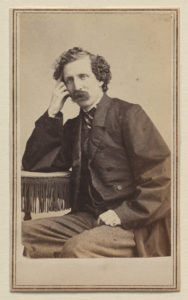

Charles Farrar Browne

(1834–1867), the most famous and beloved American humorist before

Mark Twain, with whom he has often been compared. His immortal and hugely popular “Artemus Ward” columns made their first appearance in The Cleveland Plain Dealer, of which Browne was editor in the 1850s. One of Cleveland’s schools is named for him. The dispatches, which purported to be the frank reports of an itinerant sideshow proprietor of that name, were related in realistic language (and a hilarious attempt at phonetic spelling). “My show at present consists of three moral Bares, a Kangaroo (a amoozin little Raskal—t’would make you larf yerself to deth to see the little cuss jump up and squeal), wax figgers of G. Washington, Gen. Taylor, John Bunyan, Capt. Kidd, and Dr. Webster in the act of killin Dr. Parkman, besides several miscellaneous moral wax statoots of celebrated piruts & murderers….” “Oberlin is a grate plase,” he writes of an afternoon jaunt to the nearby campus then already known as a hotbed of liberal activism. “The College opens with a prayer, and then the New York Tribune is read.”

President Lincoln was said to have savored the columns. Readers 170 years later still find themselves bursting out laughing as Ward—in language that at times anticipates

Joyce’s devilish puns—describes his encounters with everybody from early suffragettes and Shakers (“the strangest religious sex I ever met”) to free love advocates: “They didn’t wear no weskuts for the purpose (as they sed) of allowin the free air of heven to blow onto their boozums.” Intrigued by the new fad of spiritualism, Ward decides to check out a séance. “Thay axed me if thare was anbody in the Sperret land which I wood like to converse with. I sed if Bill Tompkins, who was onct my partner in the show biznis, was sober, I should like to convarse with him. ‘Is the Sperret of William Tompkins present?’ sed 1 of the long hared chaps, and there was three knox on the table. Sez I, ‘William, how goze it, Old Sweetness?’ ‘Pretty ruff, old hoss,’ he replied.”

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

If some of Ward’s observations can seem “politically incorrect” by today’s standards, it should be remembered that this is social satire. (Think only of today’s irreverent stand-up comics.) These are, after all, the observations of a fictional character who is obviously poorly “ejicated” and, by his own unblushing admission, a snake oil salesman. “Ward, to me, seems to function as a Civil War-era Stephen Colbert,” says juror Aaron Davis. “The character is a fool, a liar, and an opportunist, and willingly identifies himself as such.

I don’t think the things that come out of his mouth are meant to represent Browne’s own thoughts. I think he was a sharp observer and documenter of his time, and he lived in a time of massive racial and sexual inequality, so a lot of what he’s writing about can be difficult for us to read.” “He reflects the language and assumptions of his times,” John Carroll-based poet George Bilgere agrees. “We don’t throw out Mark Twain,” notes Matt Weinkam, “we teach what is problematic about his work right along with what is worth celebrating.”

But whether Ward is commenting on a high-flown orator at a Fourth of July celebration (“I’m a plane man. I don’t know nothin about no ded languages and am a little shaky on livin ones”) or quoting a bit of conversation overheard at a traveling production of Othello (“Betsy Jane! let us pray that our domestic bliss may never be busted up by a Iago!”), these earnestly related vignettes offer a rich glimpse of mid-19th century American life and everyday conversation as you suspect it must actually have sounded. “The Senses taker in our town bein taken sick he deppertised me to go out for him one day, and as he was too ill to give me informashun how to perceed, I was consekently compelled to go it blind. Sittin down by the road side I drawd up the follerin list of questions which I proposed to ax the peple I visited: What’s your age? Whar was you born? Air you marrid, and if so how do you like it?”

Think of Browne as a kind of 19th century Harvey Pekar.